3: World building, one concept at a time

The principles unfold

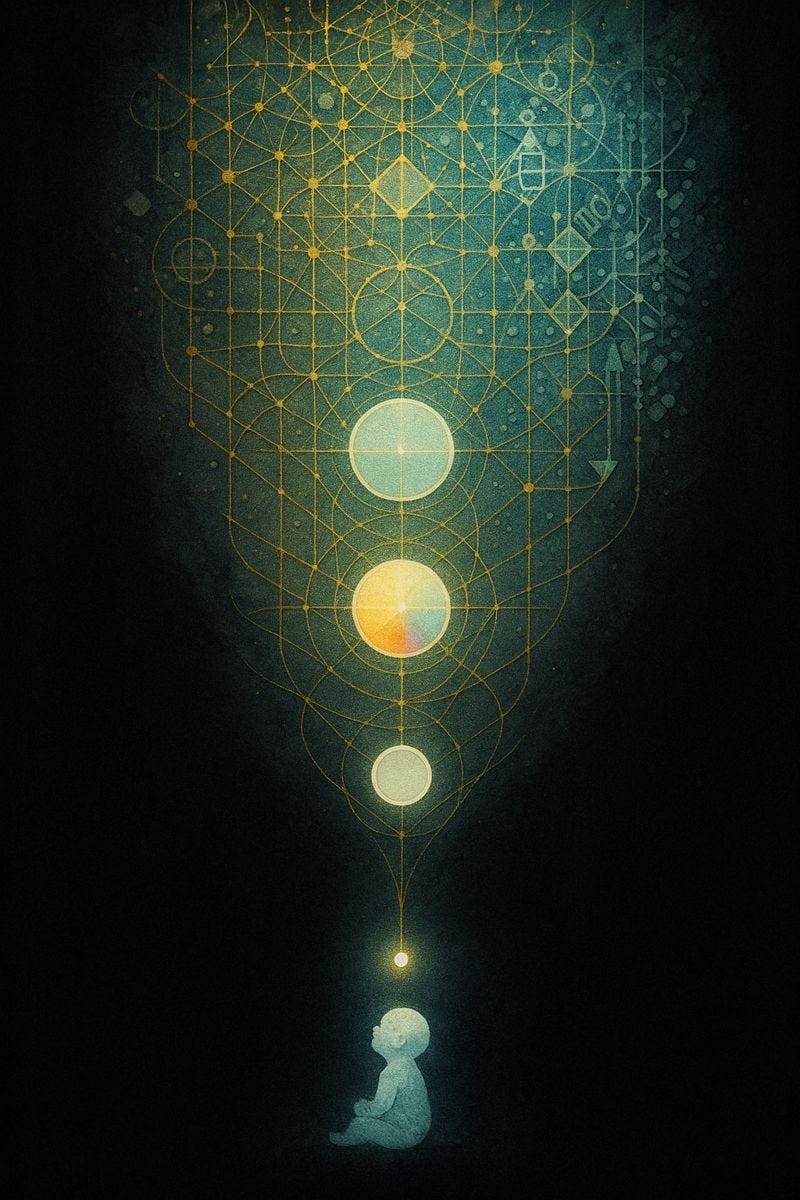

The goal of this chapter is to understand how babies and humans build a useful model of the world - and why this process reveals something profound about the nature of knowledge itself.

The Miracle of First Encounters

Let’s watch a baby encounter an apple for the first time. In that single moment, an explosion of new concepts enters their world: “apple,” “not apple,” “red,” “round,” “can eat this,” “crunchy,” “sweet” - or perhaps “don’t like this.” What seems like a simple interaction actually represents the baby adding multiple interconnected ideas to their understanding of reality.

Each new concept doesn’t exist in isolation. “Apple” connects to “food,” which connects to “hunger,” which connects to “satisfaction.” “Red” connects to other red things they’ve seen. “Round” links to balls and other circular objects. A single apple encounter weaves dozens of conceptual threads into the baby’s growing mental tapestry.

As babies mature, they grasp increasingly complex ideas. Understanding how that apple came to exist requires grasping an intricate chain: apple seed → planting → water and sunlight → tree growth → fruit development → harvesting → shipping → store → purchase → presentation to baby. A two-year-old cannot follow this chain, but the same mind that once struggled with “apple” will eventually master these abstract connections.

This progression from simple to complex happens in all learning. Consider a champion swimmer teaching a beginner. The expert’s fluid, graceful movement must be deconstructed into teachable components: breath control, hand position, kick technique, head movement, body coordination. What appears as one seamless skill is actually dozens of concepts working together.

The Challenge

Understanding how humans build these “useful models of the world” seems daunting until we realize something remarkable: we’ve all been doing this since birth. Every human mind has successfully navigated the journey from knowing almost nothing to understanding enough to survive and thrive in an incredibly complex world.

But how does this actually work? How do we go from a baby’s first glimpse of light to an adult’s ability to navigate relationships, careers, technology, and abstract ideas? If we could understand this process, we might glimpse something fundamental about how complexity emerges from simplicity - our “something to everything” principle in action.

The key insight is this: all complex understanding is built by adding one concept at a time. To understand how this remarkable process actually works, we need to isolate the fundamental mechanism. Real babies learn in a rich, chaotic environment where dozens of concepts arrive simultaneously. But what if we could slow this down and watch complexity build one carefully controlled step at a time? What if we started with the simplest possible scenario and added just one new element at a time?

Thought Experiment

So, a possible way to attempt it is to kick off a thought experiment with the blank mind of a baby and an empty universe, into which we introduce chunks of complexity iteratively.

Picture this:

The Beginning: Pure Void

Picture this - a baby floating in absolute nothingness. No light, no sound, no objects - just infinite empty space. The baby can perceive, but there’s literally nothing to perceive except the basic awareness of existing.

At this starting point, the baby’s entire understanding of reality boils down to something like: “I exist, and there’s a world around me, but I can’t see anything in it.” That’s it. The complete worldview fits in a single sentence.

Hour 1: Let There Be Light

Now imagine we introduce the first element: ambient light that can be turned on and off. Suddenly, the baby’s reality expands. Where once there was only existence and void, now there are two possible states: bright world and dark world.

The baby can now form multiple thoughts: “The world is bright,” “The world is dark,” “I can see when it’s bright,” “I can’t see when it’s dark.” From one basic understanding, we’ve jumped to several distinct observations. The complexity has already multiplied.

Hour 2: The First Object

Next, we materialize a simple black ball somewhere in the baby’s field of vision. This single addition transforms everything. The baby’s reality now includes the revolutionary concept that objects can exist - or not exist - in the world.

New possibilities emerge: “I see a ball in the bright world,” “I don’t see a ball,” “The ball appeared,” “The ball disappeared.” The baby is beginning to distinguish between the world itself and things within the world. We’ve gone from a handful of thoughts to dozens.

Hour 3: The World Has Directions

Let’s give the baby the ability to turn its head and place the ball anywhere around it - front, back, left, right, up, down. This seemingly simple change creates an explosion of possibilities.

Now the baby can think: “I see the ball in front of me,” “The ball is behind me and I have to turn around,” “The ball is above me.” Each direction multiplies the previous possibilities. We’re now talking about hundreds of potential observations.

Hour 4: A Universe of Color

Here’s where things get wild. We introduce color - let’s say just 100 different shades the ball can take. Red balls, blue balls, pink balls, transparent balls.

The baby’s mind can now process thoughts like: “I see a red ball to my left in the bright world,” or “There’s a blue ball behind me.” Since color works independently of direction, every directional possibility now gets multiplied by every color possibility. We’ve just leaped from hundreds to thousands of potential thoughts.

Hour 5: The Dimension of Distance

Finally, we allow the ball to appear at different distances - very close, close, medium distance, far, very far. This adds yet another layer that combines with everything else.

The baby can now think: “I see a pink ball very close to my right,” or “There’s a blue ball far away behind me.” Every combination of color, direction, and distance becomes possible. We’re now looking at tens of thousands of potential observations.

The Explosion

And we’re just getting started. Imagine if we added:

Multiple balls: “I see three red balls and two blue ones”

Shapes: “The balls are arranged in a triangle”

Movement: “The red ball is moving toward me”

Time: “The ball was here before, now it’s there”

Each new dimension doesn’t just add to the complexity - it multiplies it. With just a dozen basic concepts, we could generate millions or billions of possible thoughts and observations.

What’s remarkable is that human babies navigate this exponential explosion of complexity with ease. Somehow, our minds are built to handle this kind of rapid scaling from simple beginnings to vast, intricate understanding.

From the absolute simplicity of “I exist” to the rich complexity of “I see three pink balls moving in a circle while two blue balls stay still in the distance” - all built from introducing one simple concept at a time.

Babies in the wild

To make this a little more real, let’s look at how the sequencing of concepts that babies pick up through their actual lives mirrors our thought experiment. They start with basic and concrete concepts that relate to their immediate environment and experiences, then keep progressing in a remarkably consistent pattern. Here’s how it typically unfolds:

Immediate Environment: Babies begin with words that describe objects and people in their immediate surroundings - “mom,” “dad,” “toy,” “bottle,” “blanket,” and “bed.” These are their foundational building blocks, just like our void and light.

Actions and Verbs: Next come words that describe actions they observe or experience - “eat,” “sleep,” “wave,” “clap,” “crawl,” “walk,” “want,” “give,” “share.” The world transforms from static objects to dynamic interactions.

Basic Needs: They learn words related to survival and comfort - “hungry,” “thirsty,” “diaper,” “bath,” “play,” and “hug.” These concepts help them navigate and communicate their essential requirements.

Emotions and Feelings: Soon they develop vocabulary for internal states - “happy,” “sad,” “excited,” “tired,” “love,” and “comfort.” This represents a leap from external observations to internal awareness.

Colors, Shapes, and Sizes: They gradually master descriptive attributes - “red,” “circle,” “big,” “small,” “square,” and “triangle.” Like our colored balls, these concepts multiply all previous understanding.

Animals and Nature: Their world expands beyond the home - “dog,” “cat,” “bird,” “tree,” “flower,” “sky,” “sun,” and “rain.” The immediate environment gives way to the wider world.

Family and Relationships: They develop understanding of social structures - “grandma,” “grandpa,” “uncle,” “aunt,” “friend.” Human connections become mapped and understood.

Expanded Vocabulary: Finally, they continue building vocabulary related to their interests, experiences, and discoveries, gradually introducing more complex concepts and abstract ideas as they grow and develop.

This sequencing isn’t arbitrary. The order matters deeply. A baby cannot learn “apple tree” before understanding “apple.” They cannot grasp “photosynthesis” before knowing “plant” and “sunlight.” Each concept requires prerequisites—simpler building blocks that must already exist in their mental model. This is the rule structure of learning itself: concepts must be introduced sequentially, with each new idea building causally on previous ones.

This also reveals why social scaffolding is essential. Babies don’t just passively absorb concepts from their environment—they need guided instruction. Parents point and name objects, demonstrate actions, provide emotional context. Without this structured sequencing, learning stalls dramatically. The tragic cases of feral children—like Genie, discovered at age 13 after years of isolation—demonstrate this powerfully. Despite intensive intervention, children deprived of this early structured exposure never fully catch up. Their window for building foundational concepts in proper sequence had closed. Learning, like the systems in Chapter 2, requires not just components but rules governing how those components combine.

What’s truly astounding is that when this progression unfolds properly - from recognizing “mom” to understanding complex social relationships and abstract concepts - it happens naturally in every healthy child. Without formal instruction, without conscious effort, babies construct increasingly sophisticated models of reality by adding one concept at a time. Each new concept doesn’t just expand their understanding linearly; it multiplies exponentially with everything they already know, creating a rich, interconnected web of knowledge that allows them to navigate an incredibly complex world with remarkable skill and joy.

Extrapolations

Notice that from our perspective all concepts the baby knows - its world model - are pre-existing concepts. The baby didn’t invent the idea of “red” or “ball” or “distance.” These concepts already existed in the world, waiting to be discovered and learned.

But here’s where it gets fascinating: every concept we take for granted was once a genuine discovery made by someone for the very first time.

Consider the concept of “zero.” Today, any child learns this as naturally as learning colors. But zero was actually invented - discovered, really - by ancient mathematicians in India around the 5th century. Before that breakthrough, entire civilizations conducted mathematics without this fundamental concept. Once discovered by a few minds, it spread person by person, generation by generation, until every schoolchild on Earth now learns it as a basic building block of arithmetic.

Or take the idea of “germs.” For thousands of years, humans got sick and died without understanding why. Then in the 1600s, people like Antonie van Leeuwenhoek first observed microorganisms through primitive microscopes. This single conceptual breakthrough - that invisible tiny creatures could cause disease - eventually transformed into our modern understanding of bacteria, viruses, antibiotics, and sanitation. What began as one person’s startling observation became foundational knowledge that every medical student now learns.

The same pattern repeats throughout history. Agriculture, writing, the wheel, electricity, DNA - each represents a moment when a human mind first grasped a new concept, then shared it with others who shared it with others, building layer upon layer until these ideas became part of humanity’s collective understanding.

This is exactly what we witnessed with our baby learning about balls and colors, just played out across centuries instead of hours. Humanity as a whole follows the same “something to everything” principle - we build our vast, complex civilization one concept at a time, each new idea combining and multiplying with everything we already know.

The baby learning that a red ball can appear “far away” mirrors how our species learned that distant stars could be analyzed through spectroscopy, or how quantum mechanics emerged from simple observations about light and energy. In both cases - individual learning and collective human knowledge - we start with basic building blocks and construct increasingly sophisticated understanding through patient, incremental discovery.

The entire edifice of human civilization, in all its staggering complexity, emerged from this single process: simple foundations, contextual rules, sequential addition leading to exponential growth. Everything from something, one concept at a time.