4: The Landscape of Thought

Mapping the pathways of human thoughts

We’ve seen how babies build complexity from simple concepts, one idea at a time. But what happens when that process continues for decades? How do we make sense of the vast collection of thoughts that make up an adult mind, and is there any underlying structure to our mental lives?

All the Thoughts We’ve Ever Had

By the time we reach age 20, the average person has had roughly 45 million thoughts (~6.2K thoughts per day). By 50, that number approaches 100 million. By the end of a long life, we’re looking at something close to 200 million distinct mental events - each one a unique moment of consciousness, a specific combination of concepts, memories, and ideas flowing through our minds.

Take a moment to consider the staggering scope of this mental activity. Every fleeting observation about the weather, every complex decision about our careers, every random memory that surfaces while brushing our teeth - all of it adds up to this enormous collection of cognitive events that, in total, represents our entire conscious experience of being human.

But here’s what’s truly remarkable: despite this vast quantity, there seems to be an underlying structure to it all. Our thoughts aren’t just random firings of neurons. They connect to each other, build on previous ideas, and follow patterns that somehow make sense to us. The question is: what does this structure actually look like?

Is there any way to understand how 200 million thoughts organize themselves into something coherent enough that we can navigate daily life, form relationships, solve problems, and make sense of the world around us?

The Challenge of Visualization

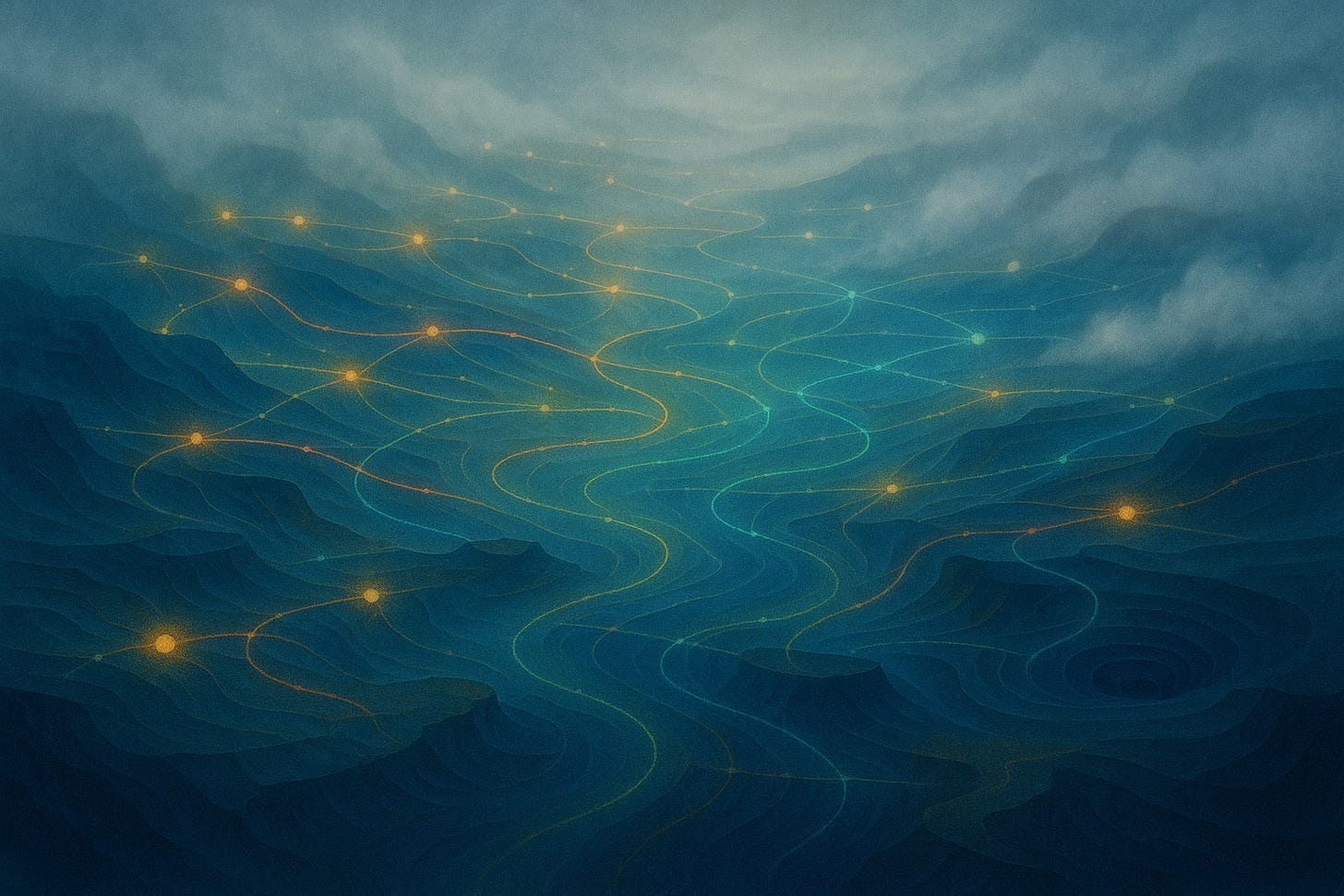

Imagine if we could see all human thoughts as paths through a vast, three-dimensional landscape of interconnected concepts. Picture each idea - “love,” “pizza,” “Monday,” “gravity” - as a glowing point of light suspended in space, connected to related concepts by invisible threads. Every thought we’ve ever had would appear as a journey from one point to another, creating a luminous trail through this conceptual universe.

This isn’t just a poetic metaphor. It’s a way to visualize something remarkable: the structure of human consciousness itself.

Mapping a Simple Thought

Let’s start with something basic. Consider the thought: “I love chocolate ice cream.”

In our conceptual landscape, this simple sentence becomes a path connecting four concept-points:

“I” (the self)

“Love” (an emotion)

“Chocolate” (a flavor/food)

“Ice cream” (a dessert)

But here’s where it gets interesting. Each of these concepts connects to dozens of others. “Love” links to “happiness,” “relationships,” “heart,” “romance.” “Chocolate” connects to “sweet,” “brown,” “candy,” “cocoa trees,” “South America.” “Ice cream” branches to “cold,” “summer,” “dairy,” “dessert,” “childhood.”

What seemed like a simple four-word thought actually represents a journey through a rich neighborhood of interconnected ideas, each carrying its own web of associations and memories.

The Explosion of Complexity

Now imagine every thought you’ve had today. Your morning observation that “the coffee is too hot” traces one path. Your afternoon realization that “this meeting could have been an email” follows another. Your evening plan to “call mom tonight” creates yet another trail through the conceptual space.

According to researchers, we average about 6,000 thoughts per day. Over a lifetime, that’s roughly 200 million unique paths through our personal concept landscape. Each path builds on previous journeys, creating well-worn routes between frequently connected ideas and occasionally blazing new trails to previously unlinked concepts.

Despite having access to roughly the same basic concepts - the words and ideas available in our language and culture - each person’s lifetime collection of thought-paths creates a unique signature. Your conceptual landscape looks different from everyone else’s because you’ve traveled different routes through it.

Individual Signatures in Shared Space

Consider two people encountering the concept “rain.”

A farmer might immediately connect it to “crops,” “growth,” “income,” “weather patterns,” and “seasons.” Their thought-path through rain-related concepts draws heavily from agricultural knowledge and economic concerns. A child might link rain to “puddles,” “staying inside,” “umbrellas,” “rainbow,” and “playing.” Their path emphasizes discovery, play, and immediate sensory experience.

Both navigate the same conceptual territory - both know what rain is - but their thought-trails reveal completely different ways of understanding and relating to this simple concept.

But thought doesn’t flow freely through this landscape. Just as physical terrain has features that guide and restrict movement, our conceptual landscape has forces that shape which pathways we can and do traverse.

Habits, cultural conditioning, incentives, and cognitive biases act like gravitational wells, making certain pathways easy and natural to follow while requiring conscious effort to escape. We tend to think in patterns we’ve thought before, returning again and again to comfortable conceptual neighborhoods even when more valuable territory lies elsewhere.

Areas of the concept landscape where we lack knowledge appear hazy and indistinct like fog. We can sense that concepts like “quantum mechanics” or “Mandarin grammar” exist out there somewhere, but without foundational understanding, we cannot see the pathways leading to them or navigate through them with any confidence.

There are edges to our understanding - hard boundaries where our mental models simply cannot go. A person who has never experienced color cannot truly navigate concepts related to “red” or “blue.” Someone without mathematical training hits a cliff edge when encountering differential equations. These aren’t just gaps in knowledge; they’re fundamental limits on which territories we can access unless there is a path for us to climb the cliff.

Our attention remains finite. We can only explore a tiny sliver of what’s possible in this vast landscape. The terrain itself pushes back, constraining our exploration.

The Collective Landscape

Here’s where our individual concept graphs become something much larger. Every human who has ever lived has contributed their unique thought-paths to an enormous, collective conceptual landscape. This shared space contains not just the concepts available to any individual, but the sum total of all possible connections humans have ever made between ideas.

When ancient mathematicians in India first connected “nothing” to “number” to create the concept of zero, they carved a new pathway through the collective landscape - one that billions of people now travel routinely. When Darwin linked “species,” “time,” “variation,” and “survival,” he blazed a trail that fundamentally changed how we navigate concepts related to life itself.

Every scientific discovery, artistic innovation, and philosophical insight represents someone finding a new route through our shared conceptual space - or connecting previously distant regions for the first time.

The Beauty of the System

What makes this visualization so powerful is how it reveals the “something to everything” principle at work in human consciousness. We start with individual concepts - simple points of light in the landscape - but through the countless ways we can connect and traverse between them, we generate the infinite complexity of human thought and knowledge.

The same framework allows a child to think “The ball falls when I fling it” and also enables Einstein to think “energy equals mass times the speed of light squared, E = m * c^2.” The difference is in starter set of building blocks and the sophisticated paths carved through the conceptual landscape by education, experience, and insight.

The Question of Choice

This brings us to a crucial realization. If human conscious experience operates by navigating through a landscape of interconnected concepts, and if the paths we choose to travel shape who we become and how we understand the world, then perhaps the most important question we can ask is this:

Given our limited lifespans, which routes should we tread on? Are we optimizing for truth, meaning, belonging, novelty, utility? Not all paths are equally valuable. Some lead to dead ends or circle back on themselves. Others open up vast new territories of understanding. Some are well-traveled highways of conventional wisdom, while others are barely visible trails leading to profound insights. How do we notice when gravity and fog, not our goals are steering us?

This choice is the core epistemological act—the routes we pick determine what we can know, how we grow, and how we make sense of the world.